Learn Active Listening the Formula, Examples & Steps to Follow

An easy way to understand people’s point of view. Watch examples, learn pitfalls and top tips. Use our step-by-step guide in the workplace and beyond!

Wouldn’t it be nice if you could read people’s minds?

No two people see the world in the same way. Each person’s viewpoint is unique. It’s rooted in their background and life experiences. We might think that we know what matters to people. But when we assume, we often get it wrong.

Most of us need to communicate with many people every day. At the workplace and beyond. For those of us without magical powers, what’s our best option? How can we understand people’s point of view?

The Swiss Army Knife of communication

I’ve spent the last decade learning about communication skills. Of all the techniques I’ve learned (and taught), one stands out: active listening. I call it the Swiss Army Knife of communication. You can use it whenever you need to build understanding. At work, at home, on the street. In a meeting or in a conflict. With CEOs and small children. (Yes, I’ve used it with both.)

In this post I’m going to tell you what active listening is. Not just by describing it. I’m also going to show you how it works with real examples. I’ll share a formula you can use to get started today. And instructions for how to practise with a friend. You’ll learn the pitfalls to avoid and top tips to remember.

Let’s get started!

What is active listening?

Active listening is a way to understand someone’s point of view. While you listen, you ignore your own thoughts and ideas. Instead, you focus on what’s happening to them. Then you reflect back what you heard in your own words. And check whether you got it right. They’ll either clarify or say more.

Then you start the process over again. Listen, reflect back, check. The cycle continues for as long as it needs to.

This process isn’t about getting information. Sure, you need to establish the facts. But the facts aren’t the point. Your goal is to imagine what it’s like to be them. To connect with the feelings and needs which influence their words. This creates empathy. Which leads to trust.

Listening is a powerful tool. As long as you commit to giving it a go, I guarantee that you’ll learn something. You might even find that the other person learns something about themselves! When people listen to us, it changes how we see our own situation.

Have you ever noticed someone say, “it sounds like,” or “I’m hearing that,” when they talk to you? If so, they were probably using this technique.

It’s the most versatile communication skill that I know. It can adapt to almost any situation. And it’s easy to learn. If you want to improve your soft skills, it’s a great place to start.

Origin of the technique

American psychologists Carl Rogers and Richard Farson coined the term “active listening” in 1957. From their article:

Despite the popular notion that listening is a passive approach, clinical and research evidence… shows that sensitive listening is a most effective agent for individual personality change and group development. Listening brings about changes in peoples' attitudes toward themselves and others… People who have been listened to in this new and special way become more emotionally mature, more open to their experiences, less defensive, more democratic, and less authoritarian.

Although the technique came from psychotherapy, it’s now used in business, education and beyond.

The formula

The active listening formula is simple:

- Ask an open question. (Like, “how are things going for you?”)

- Listen. As they speak, try to imagine what it’s like to be them. Don’t interrupt, unless it’s essential for you to understand (see below.)

- When they stop, you can either say, “tell me more about that,” and return to step 2, or …

- Reflect back. Say, “it sounds like you…… because ……”. Fill in the blanks to explain how you think they see the situation, and why. Be sure to use your own words. Then say, “did I get that right?”

- They will either clarify (“not quite…”) or share more detail. Return to step 2.

Continue this process for as long as you need to. Note that when you use this formula, conversations can go deep. Some take a long time. Other times, you’ll get clarity and move on.

Don’t try to get it right

A common error is trying to get it exactly right. Unless you can read people’s minds, this is impossible. You’re allowed to make mistakes, as long as the person can see that you’re trying. In fact, if they never say, “not quite, let me try again…,” it’s not a good sign. It means that you aren’t taking enough risks when you reflect back. Aim to guess how they’re feeling and commit to giving it a go. They will be happy to correct you if they believe that you’re trying to understand.

When is it OK to interrupt?

This technique works by subverting standard social etiquette. The normal rules dictate that we take turns. I talk about myself, then you talk about yourself, etc. Active listening changes that. You are listening, they are talking. We do not take turns.

You need to work hard to maintain these unusual rules. Your partner will try to give you a turn, because that’s the normal rule. When you say, “tell me more about that,” you’re handing them your turn. The same goes with, “it sounds like… .”

This means that interrupting is dangerous. It’s likely that your partner will interpret it as you taking your turn back. Which is why it’s only OK to interrupt when there’s no other way for you to continue listening. Usually, that’s when you don’t understand what they’ve said.

For example, imagine they use jargon or a technical term that you don’t know. Or you miss so many words that you can’t follow the logic. If you can’t figure it out, it’s time to interrupt. Do it as fast as possible, and make it clear why.

For example: “Can I ask, what does BAU mean?” If necessary, reflect back once more to confirm you’ve understood. And then encourage them to keep talking.

When can you use it?

I call active listening the Swiss Army Knife of communication. That’s because it’s a versatile technique. You can use it whenever you need to understand someone better. Or build trust. Or when you want to help someone without giving them advice. You can use it with:

- friends and family

- colleagues

- your boss

- people you don’t know

- children

You can also use it places you might not expect. Like when you’re involved in a conflict. Or if you need to get clarity when you’re working with a large group. Or in a crisis, when you need information as quickly as possible.

Sometimes you’ll make it clear that you’re using a communication technique. For example, in a one-to-one meeting at work. Or when you’re talking to your friend who’s having a difficult time. In these situations, other people might notice you saying, “it sounds like,” and realise that you’re using active listening.

Other times, you can use the technique without it being obvious. Once you learn and practise the procedure, you can adapt it. You’ll be able to include it in normal conversations. The exact words aren’t important. It’s the process that matters.

When not to use it

When I run communication courses people sometimes think I’m telling them to use active listening all the time. But I’m not. If you only ever listened, you’d never eat!

Think of listening as a mode of communication. One of several modes that you switch between during the day. Sometimes you want to express yourself or get your needs met. Other times you want to interact with people on a surface level. For example, at the water cooler:

Me: How was your weekend?

Colleague: Great, thanks. We went to a restaurant.

Me: Sounds lovely. We had some friends around…

This is a superficial conversation where we take turns to talk about ourselves. There’s nothing wrong with this! In fact, if I tried active listening in this situation, my colleague might find it awkward. It’s the wrong approach for the context.

Listening may not be the best choice when you:

- have unmet needs (like feeling hungry or tired)

- want to stand up for your interests

- don’t have time to talk, or the right space

- don’t feel comfortable with the person

- sense that the person doesn’t want to open up

Benefits of active listening

The benefits of active listening include:

- building trust through empathy

- finding out what matters to people

- helping people without giving them advice

- you don’t need background knowledge

- you can use it with anyone

Let’s discuss each in turn.

Build trust through empathy

Trust is essential to healthy relationships. This technique helps you to build it through empathy.

When you listen, you look out for what’s underneath the words. Things like nuance, tone, or any clues that suggest how they feel. (Some people call this nonverbal communication—the things that we don’t say directly.) The trick is to imagine what it’s like to be them. And then to reflect that back.

You’ll know you’ve achieved empathy when:

- you guess how the person feels based on what they said,

- you reflect it back in your own words, and

- they say that you got it right, and look relieved.

When this happens, you’ve connected on a deeper level than you would during a normal conversation. This builds trust.

Find out what matters to people

What matters to other people isn’t obvious. When we assume that we care about the same things, we tend to get it wrong

For example, when someone is upset about something, there’s always a reason. Something specific that they care about. But that reason may not be obvious to you.

Imagine your colleague tells you that they missed a train. You sense that they’re unhappy about this, but you don’t know why. Yet. It could be because:

- they’re going to miss an important meeting

- the next train will be crowded so they won’t be able to sit down

- they’ll need to buy a new ticket

- they like to be seen as punctual

- …or hundreds of other possible reasons.

When people understand what matters to us, we feel more connected to them. We feel calmer, even when we’re experiencing difficulty. Some people call this “feeling seen.” Active listening lets you find out what matters to people. Instead of assuming or guessing. This is essential if you want to understand their point of view. It shows you where they’re coming from.

Help people without giving them advice

When people tell us about their problems, it’s tempting to try to fix them. One common way to do this is giving advice. But this is often unhelpful because:

- The person isn’t sharing their problem so you can fix it. It’s more likely that they want to get it off their chest. Or discuss it with you.

- Even if they do want you to make their problem go away, your advice is unlikely to help. You don’t have enough information.

If it’s such a bad idea to give advice, why are we tempted to do it? It’s because we feel uncomfortable when we hear about another person’s misfortune. This is because:

- we don’t like the emotions it brings up, and we want to push them away, or

- hearing about their unresolved difficulties reminds us of our own.

When people give advice they’re trying to help. You can redirect this impulse—to help people—with active listening. Next time you feel the urge to fix someone’s problem, try listening instead. You may even find that they fix their own problem—or at least come up with a next step—by talking it through with you.

You don’t need background knowledge

Active listening doesn’t call for any background knowledge. You don’t need to know the person. Or understand their job. Or study the history of their situation. Remember, they are the world expert in themselves. As long as you pay attention to what they say, you’ll have all the information you need.

Imagine you have a friend who is an accomplished brain surgeon. They want to talk to you about a problem at work. Do you panic? Politely refuse? Remind them that your only medical knowledge comes from watching hospital dramas?

No. You don’t panic. Your friend isn’t coming to you for help with their next life-saving operation. They want to talk about human stuff. Conflicts, dramas, dilemmas. If you need technical information to understand what’s going on, they’ll explain it to you. (If you’re unsure, ask.) They aren’t coming to you for your knowledge or experience. They need you to listen, to understand.

When you realise that you don’t need knowledge to listen effectively, it can be freeing. It means you have everything you need to connect with anyone you meet. As long as you have enough energy and space to listen, you can help.

Use it with anyone

This also means that you can use the technique with anyone. Someone you meet on the street. The person behind the airport counter. The stakeholder at work who wants to block your project. Your friend’s kids.

Once you learn the formula and practise it, you’ll find yourself using it all over. Whenever you see an opportunity to improve understanding. Without thinking about it you’ll say, “it sounds like…”. Eventually it becomes automatic. Your own Swiss Army Knife, always with you, ready to use.

Examples of active listening

You might be thinking: this sounds great. But what does it look like in real life? Here are some examples.

How we normally respond

The examples work by comparing active listening to the ways we normally respond. In a normal conversation, we might respond by:

- Talking about ourselves. This is where we take turns to share our own experiences. We try to make them relevant to what the other person said. I call this, “that reminds me.”

- Fixing people’s problems. When people tell us about their problems, we want to fix them. We might offer suggestions, solutions or advice. I call this, “have you considered?”

When we’re in conflict with someone, we might respond:

- Defensively. For example, we might deflect criticism by saying, “I’ve already addressed your concerns.” Or we might try to ignore their concerns with a fake expression of sympathy: “I’m sorry you feel that way, but…”

People use these responses a lot. In a typical workplace you’ll hear them many times per day. And they have something else in common. All of them cut you off from the other person.

In contrast, active listening connects you.

Example 1: Someone you know

Imagine I’m having a conversation with a colleague called Jon:

Me: How has your week been?

Jon: It’s been a bit of a mixed bag actually. My boss says I’m doing a good job. But I’m having problems with my main project. The legal department want to put disclaimers everywhere. I’m worried that it’s going to ruin the whole experience! Plus I don’t know how we’re going to ship on time…

How we normally respond

A normal response (talking about myself):

Me: That reminds me of when I was trying to move house. I had to spend such a long time dealing with solicitors and paperwork and everything. It’s such a drag when you’re trying to get something simple done. You know?

Another common response is trying to fix their problem:

Me: Have you considered going straight to the General Counsel? That’s what I do when I have trouble with lawyers. They’ve got to realise that they work for the company, not the other way around. Know what I mean?

Active listening

Here’s what active listening looks like:

Me: It sounds like you’ve got mixed emotions at the moment. On the one hand, you’re happy that your boss says you’re doing a good job. But you’re questioning that, given the problems you’re having with Legal. Did I get that right?

Jon: Yeah, that’s it. They’re telling me I’m doing a great job. But if I’m doing so well, why can’t I resolve these issues with Legal? I’m not sure what to do next.

Me: Oh, mate. It sounds like you’re feeling stuck. Because while you want to do a good job, you can’t see a way to do what Legal are asking while still shipping on time. Did I get that right?

Jon: Not exactly. I’m conflicted. I want to believe what my boss is telling me, but it doesn’t figure. Either she doesn’t know what’s happening with Legal, or…

Me: It sounds like you’re unsure whether your boss is being completely honest with you. Is that right?

Jon: I hadn’t thought about it that way. But you’re right. She’s not being frank with me. It’s nice to be told I’m doing a good job, but if she won’t back me up when legal throw in new requirements at the 11th hour…

Me: You were hoping for more support from your boss?

Jon: That’s what’s bothering me, yes. I know there’s a way through this, but I can’t do it on my own. Support is exactly it.

Me: Tell me more about that.

Jon: Well, I can resolve a lot by myself. I’m used to sitting down with Legal and finding out what they really need. But it takes a lot of time. They’ve come in at the last minute and something’s got to give. My boss mentioned that the CEO is asking about delivery dates. I need some backup from her if we’re going to ship on time. You know what? I’m going to book in a one-to-one with my boss right now. To talk this through and ask for some backup. Thanks for the chat!

Me: You’re welcome.

In this example, Jon was able to solve his own problem. By listening, I helped him without giving advice.

Example 2: Building rapport

Imagine I’m trying to build rapport with my new client, Jon:

Me: How are things going with you at the moment?

Jon: Things are going well for us, thanks. We’re on track to get our new ride sharing apps into the app stores ready for Q3. All we’re waiting for now is the translations.

How we normally respond

Here’s a normal, “that reminds me,” response:

Me: It sounds like our brochures. We had the copy ready to go weeks ago. But we’re still waiting for sign off from stakeholders.

Active listening

Here’s how it works with active listening:

Me: Does this mean you’re expanding into new markets?

Jon: Yes! It’s an exciting development for us. We’ve got solid market share here in the UK, but not much elsewhere. I’m particularly hopeful about Germany. Although I’m a bit concerned about how the concepts are going to translate…

Me: Because of the longer words?

Jon: Part of it’s the language itself, yes. But it’s more the cultural side I’m worried about. Our app is all about sharing with friends and colleagues. I’ve seen the market research and it should work fine in other countries. But you can never be sure until people are using it, you know?

Me: It sounds like you’re excited to scale your services to places like Germany. And at the same time you’re concerned about whether the ways people use it here will translate to other cultures. Did I get that right?

Jon: Yeah. For example we have this popular feature on the app. It’s called “ride with a mate.” For whatever reason it strikes a chord with our customers. We’ve been told there’s a way to make this feature work in all the markets we’re targeting. But I want to make sure that it feels right.

Me: It sounds like it’s not enough for you to just translate the app into German. Because you want your service to really click with people. To enrich their lives in some way. I guess because you value the community side and sharing. Did I get that right?

Jon: Yeah, that’s spot on. Community is really important to me. I don’t want to make yet another ride-sharing app. I want our apps to make a difference.

In this example, I was able to get Jon talking about what he values. As well as his challenges and hopes for success. All through listening and reflecting back.

Example 3: In a conflict

Imagine I’m presenting to a room full of Very Important People in my company. It’s about my latest project:

Me: I’m excited to update you all on our new digital expenses project! As you know, this is part of the CEO’s digital transformation scheme. We’re replacing onerous paper expense forms with a simple smartphone app. It’s going to save a lot of time, reduce emissions… look, you can even take a photo of the receipt on your phone!

Jon: [interrupting] Jonathan, let me stop you there. As Director of HR, of course I fully support the CEO’s digital transformation scheme. At the same time, I’ve made it clear to you that the approach you’re taking is flawed! In fact my team sent you a list of issues with this approach and I don’t think we’ve heard back from you.

How we normally respond

Here’s a normal, defensive response:

Me: Jon, I’m aware of your concerns and as I’ve explained to you before, we’re going to make sure the system works for HR. It will work for everyone! Right now I’d like to share progress with the team…

Jon: But why haven’t you responded to my team’s questions?

Me: We’ve, umm… we’ve been busy.

Active listening

Here’s how it works with active listening:

Me: Jon, thanks for raising these issues. I know we need to get the whole company on board to make this project a success. So I value your input. It sounds like while you support the digital transformation agenda, you have some concerns about how we’re implementing expenses. Did I get that right?

Jon: Yes, that’s right. As I said, the approach is flawed! The current expenses procedure is based on years of considered judgements. You’re riding roughshod over a system that works very well.

Me: It sounds like you think we’re dismantling the current system without understanding why it’s designed like that. Did I get that right?

Jon: Yes. For example the sign-off process. Under the current system, all spending is carefully controlled. With line managers approving budgets. It creates an audit trail and promotes efficiency. In your digital system, anyone can spend anything! How am I going to keep track of it all?

Me: It sounds like you’re worried that the new system won’t allow you to keep track of what people are spending. Because it’s important to you that we control spend and that managers know what their staff are doing. Is that right?

Jon: Yes, you need to come up with a new approach. Moving to digital doesn’t mean throwing away what works.

Me: Thanks for your input, Jon. We’re still designing and tweaking the system. Your feedback helps with that. I’ll make sure we include a way for you to keep track of your team’s spending.

In this example, clearly the HR Director isn’t happy. But active listening has helped us get a better idea of what’s bothering him. This means we can address his concerns and hopefully win him over.

How it works

Active listening helps people to explore and think through their experiences.

People don’t always know how they feel. Even about issues that are important to them. And even when they can name an emotion, they may not have unpacked why they feel that way. (Related: don’t ask, “how does that make you feel?” See pitfalls below.)

It’s hard to decide what to do about a problem when you haven’t figured out how you feel about it. That’s where listening comes in.

Most of us need help to think things through. We don’t want other people to decide for us. But support can help us make a decision.

When you use active listening, you provide this support. You make yourself available. You devote time, energy and attention. It’s not about your knowledge or life experience. It’s about empathy. Imagining what it’s like to be them. And it’s also about generosity. When you reflect back, you offer a gift. “This is what I’m hearing. This is what seems important to you. Here’s why. Did I get that right?”

Why it’s called “active”

Earlier I quoted the two psychologists who invented this approach. They noted that people tend to think of listening as passive. Now, this is true in normal conversations. Where people are waiting for their turn to speak.

But in the conversations I’ve described in this post, listening changes the person. From the quote:

…people who have been listened to in this… way become more emotionally mature, more open to their experiences, less defensive…

It’s counter-intuitive. We think of listening as passive. We want to help. So we try fixing people or giving them advice. But this doesn’t produce change. Because your advice isn’t useful. So people can’t act on it. But it you instead listen in the way I’ve described… the person will change.

In concrete terms. Often people solve their own problems when you listen to them in this way. You’ve enabled that change through active listening.

When people learn to use this technique, they realise why it’s called “active”. It’s a lot of work! You need to pay attention to what people say. You need to guess how they feel, and why. And you have to take a risk, as you reflect back what’s important to them. Many times over.

It’s worth it, though.

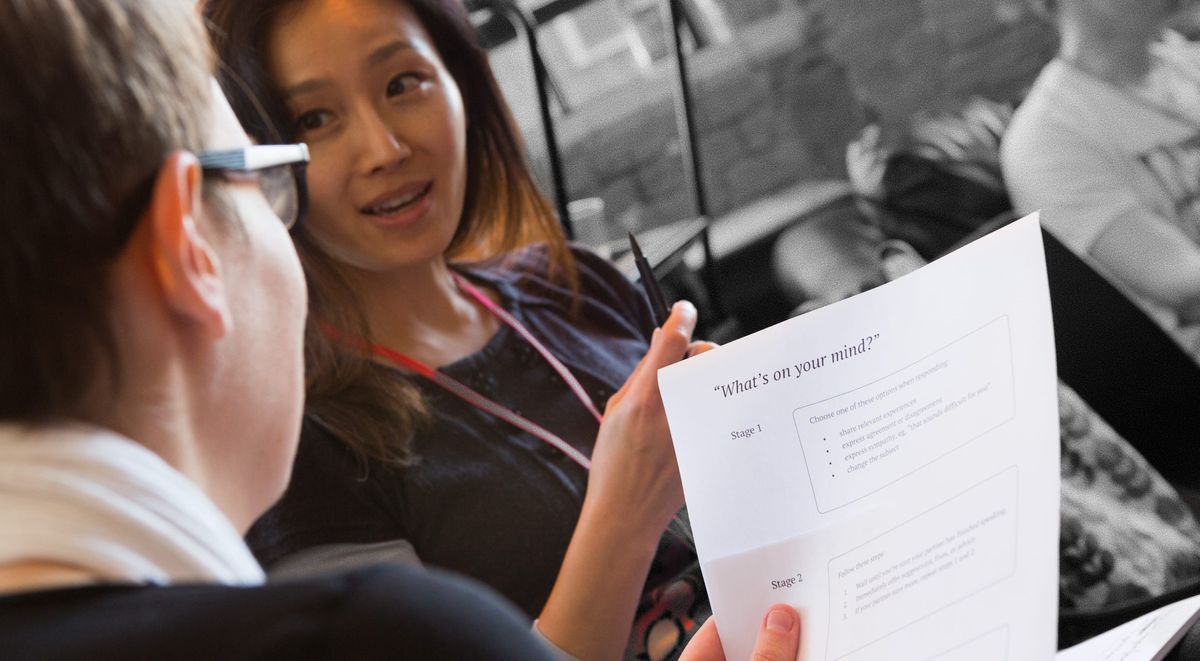

How to practise

The best way to practise active listening is with a partner. This can be in person or by video call. It can be a friend, colleague or family member. It takes 15 minutes.

Instructions for working with a friend

Start with two ways that we normally respond. Ask your friend how things are going, and then:

- Share relevant experiences from your own life. (“That reminds me...”)

- Start again with the same question. This time, offer suggestions or advice. (“Have you considered?”)

Discuss how each of these felt.

Now try active listening. Ask the same question. This time, use the formula above. When you finish, discuss how it went:

- Where did the conversation go this time? How did it compare to the other techniques?

- What was difficult about active listening?

- Which approach did your friend prefer?

If you have time, swap roles. This lets your friend try out the techniques. And it helps you understand what it’s like to be on the receiving end.

Pitfalls & top tips

Here are some tips and gotchas to get you started.

Pitfalls to avoid

Here are three pitfalls to avoid when you’re learning this technique:

- Saying, “I understand” or “I hear you.” This seems like a nice thing to say. The problem is, you don’t know whether you understand. It’s not up to you to decide that. Instead, ask whether you’ve understood. Tell the person what you heard and check if you got it right.

- Saying, “how does that make you feel?” Often people aren’t sure how they feel. Instead of asking them, guess. Imagine you were in their situation. How would you feel? Then say, “I guess you’re feeling <anxious/excited/sad/happy/relieved> because <reasons>. Did I get that right?”

- Pretending to listen without committing. For example, saying “tell me more” a lot of times without paraphrasing what you heard. Or repeating the exact words the person said instead of using your own words.

Top tips to remember

My three top tips for active listening are:

- Leave space. Your number one job is to get your partner to say more. One way to do this is to leave larger gaps than normal. This shows that you don’t need to take the next conversational “turn”. Try counting to five in your head before you respond. This will signal that you want to hear more.

- Take the leap. Doing active listening well means being ready to get it wrong! Don’t be afraid to guess what’s happening for your partner. As long as you say, “it sounds like...”, they’ll be happy to correct you. In fact, it’s a good thing if you get it wrong sometimes. It shows you’re trying, and people appreciate it when you try to understand them.

- Practise! Nobody was born with excellent communication skills. We all need to keep learning. The easiest way is to work with a partner. You can also practise in everyday life. Whenever you need to understand someone, try saying, “it sounds like...” and see where it goes.

What are you waiting for? Give it a go, and let me know how you get on.